Vienna's Secret Life Between the Waltzes

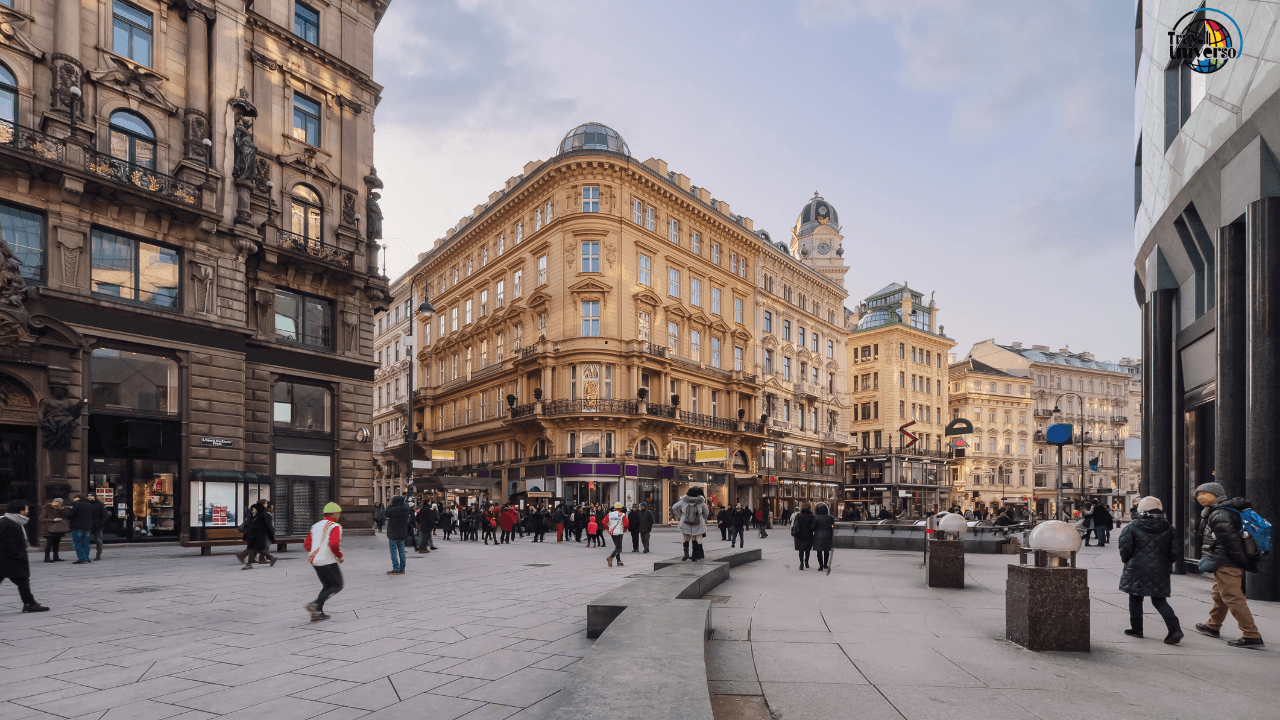

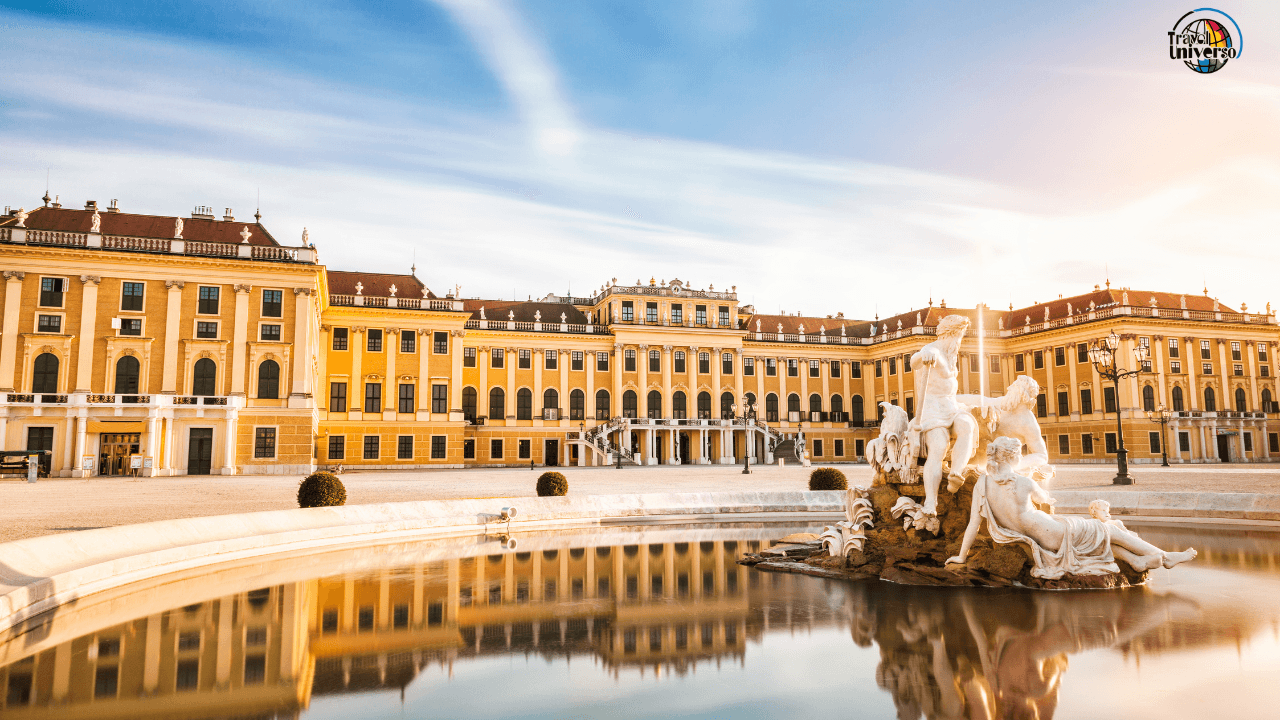

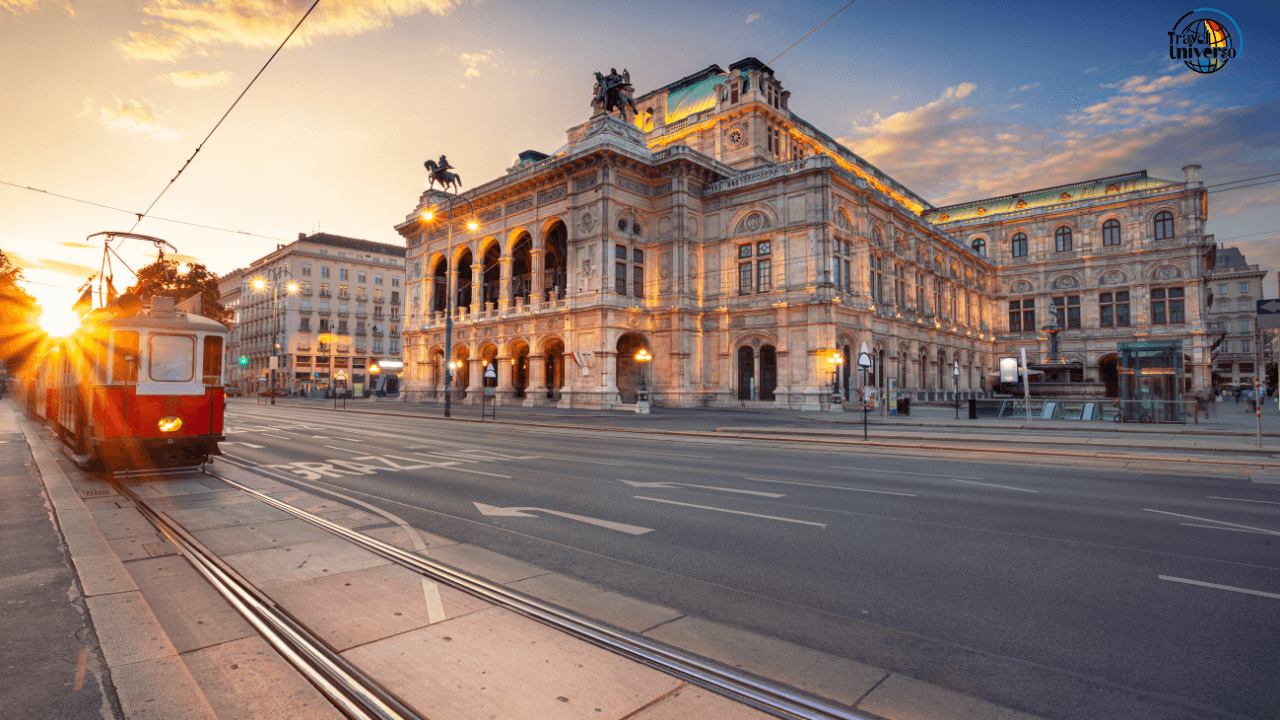

Vienna sells itself on imperial grandeur—gilded palaces, Mozart concerts in period costume, Sachertorte in marble-clad cafés. And yes, that Vienna exists, perfectly preserved like a museum exhibit of Habsburg glory. But there's another Vienna, one that most visitors miss entirely: a city of hidden courtyards and workers' palaces, of wine taverns in vineyard-covered hills, of brutal Cold War architecture standing defiantly beside Baroque churches, of a working-class soul that survives beneath the aristocratic veneer.

This is the Vienna that Viennese actually inhabit—a city that's simultaneously obsessed with its past and quietly radical, formal yet irreverent, elegant but never precious. And discovering it requires ignoring almost everything the tourist board tells you to do.

The Heuriger Pilgrimage

Every guidebook mentions Vienna's Heurigen—wine taverns in the city's vineyard districts—but almost none explain how they actually work or why they matter to Viennese identity.

Here's what you need to know: Heurigen aren't restaurants. They're a centuries-old tradition where winemakers sell their own "new wine" (heuriger) directly from their vineyards, accompanied by cold buffets. The real ones are family operations in the hills of Grinzing, Neustift am Walde, Stammersdorf, and Nussdorf, marked by a pine branch (Föhrenbusch) hung above the door—an ancient signal that new wine is ready.

Skip the tourist traps on Grinzing's main drag entirely. Instead, take tram 31 to its terminus in Neuwaldegg, then walk uphill through actual vineyards to family-run Heurigen like Hajszan or Mayer am Nussberg. Arrive around 6 PM on a weekday. You'll find Viennese families, elderly couples, groups of friends—locals treating this as their living room.

The ritual: grab a table (they're communal, you'll share), order wine by the "Achtel" (eighth-liter glass) or "Viertel" (quarter-liter), then visit the buffet. Load your plate with house-made spreads (Liptauer cheese, pork lard with cracklings), various wursts, pickled vegetables, and dark bread. Pay by weight or item. Return to your table. Repeat.

The wine is intentionally simple—young, fresh, often cloudy, designed for easy drinking and conversation. The Viennese will sit for hours, eating slowly, drinking steadily, talking. This isn't about getting drunk; it's about Gemütlichkeit—that untranslatable concept of coziness, congeniality, and unhurried pleasure.

Stay until dark. Walk back down through the vineyards as Vienna's lights spread below you. This is when you'll understand that Vienna isn't just a museum city—it's a place where medieval traditions persist because they're genuinely pleasant, not because they're profitable for tourism.

Gemeindebau: The Other Vienna

Between 1919 and 1934, Socialist Vienna built something revolutionary: massive public housing complexes (Gemeindebauten) that provided quality apartments for workers, complete with shared courtyards, laundries, kindergartens, libraries, and medical clinics. These "workers' palaces" housed hundreds of thousands and represented a radical reimagining of urban life.

Most tourists never see them. That's a mistake.

Take the U4 to Heiligenstadt and visit the Karl-Marx-Hof—over a kilometer long, housing 5,000 people, decorated with heroic worker statues and socialist symbolism. It's not a museum; people live here. Walk through the archways into the interior courtyards—vast green spaces where residents garden, children play, and elderly folks sit on benches. The scale is staggering, the architecture both brutal and idealistic.

Then explore the neighborhood around it. This is working-class Vienna: bakeries selling Wuchtel (sweet buns), Turkish vegetable markets, Vietnamese restaurants, kebab shops, everyday life far removed from Ringstrasse grandeur. Stop at a Würstelstand (sausage stand) for a Käsekrainer (cheese-filled sausage) and a Ottakringer beer. These ubiquitous stands—Vienna has hundreds—are the city's true democratic spaces, where businesspeople, construction workers, and late-night revelers all stand at the same counter, eating with their hands.

Visit more Gemeindebauten: the Reumannhof, the Goethehof, the Sandleitenhof. Each represents a different architectural vision of utopia. Some were literally fortresses—during the Austrian Civil War of 1934, workers barricaded themselves in these complexes and fought right-wing forces for days.

This history—of Red Vienna, of class struggle, of radical social housing—exists in parallel to imperial Vienna. Both are real. Both define the city. But only one appears in most guidebooks.

The Café as Office, Living Room, and Therapy

Yes, Vienna's coffeehouse culture is famous, but most tourists get it wrong. They visit Café Central or Café Sacher, take photos of chandeliers, order overpriced cake, and leave thinking they've experienced something authentic.

Real coffeehouse culture is slower, stranger, and more melancholic.

Find a neighborhood café—not a tourist landmark, just a local institution. Café Ritter in Mariahilf, Café Sperl in Neubau, Café Hawelka open until late near Stephansplatz. Arrive mid-morning on a weekday. Order a Melange (coffee with steamed milk) or a Kleiner Brauner (small coffee with a bit of cream). The waiter brings it on a silver tray with a glass of water, and here's the crucial part: you can now sit there for four hours if you want. Seriously. Order nothing else. Nobody will rush you.

Look around. That elderly man reading four newspapers simultaneously? He comes every day, has for decades. The intense young woman filling notebook after notebook? She's writing her dissertation. The group playing cards in the corner? They meet here every Tuesday. The solitary figure staring into space? That's perfectly acceptable too.

Viennese coffeehouse culture isn't about coffee—it's about having a public space to be private, to read, think, write, observe, or simply exist without purpose. It's a civic institution predicated on the idea that people need somewhere to go that isn't work or home, where time moves differently, where you're alone but not lonely.

Try it. Bring a book. Sit. Watch Vienna happen around you. Feel your American/British/Australian obsession with productivity slowly dissolve. This is the Viennese art of cultivated melancholy—recognizing that life is fundamentally bittersweet, that pleasure and sadness coexist, that sitting quietly with your thoughts is not wasting time but rather living deliberately.

The city that invented psychoanalysis understands: sometimes you just need to sit with yourself.

Walk the Gürtel After Dark

The Gürtel—Vienna's outer ring road—follows the path of the old city walls, now home to elevated U-Bahn tracks, immigrant neighborhoods, and nightlife that feels nothing like imperial Vienna.

This is where Vienna gets gritty and real. Turkish restaurants and Arab bakeries line the streets. Under the U-Bahn arches, clubs and bars create a subterranean nightlife scene: live music venues, punk bars, techno clubs. Places like Chelsea, Rhiz, and B72 host everything from experimental electronic music to local indie bands.

Walk from Nussdorfer Strasse down to Westbahnhof on a Friday night. You'll pass from Turkish Vienna to Balkan Vienna to hip Vienna to seedier Vienna—all within a few kilometers. It's louder, messier, more diverse, and infinitely more interesting than the sanitized first district.

Stop at a Kebap stand (yes, Kebap—that's how Austrians spell it) for a late-night Döner. The Turkish and Arab communities have been in Vienna for generations now, and their food is as Viennese as schnitzel—though the tourism industry rarely acknowledges it.

This is also where you'll see Vienna's other architectural identity: postwar Modernism and Brutalism. The Flak Towers—massive anti-aircraft fortifications from WWII—loom like concrete mountains, too solid to demolish, now repurposed as climbing walls and aquariums. The Wohnpark Alt-Erlaa—a utopian 1970s housing complex—rises like a vision from Blade Runner. These structures aren't beautiful in a traditional sense, but they're honest, and they tell truths about Vienna that Schönbrunn Palace never will.

The Naschmarkt Secret

Everyone visits the Naschmarkt—Vienna's famous food market—but most visit it wrong. They come at noon on Saturday when it's packed with tourists, buy overpriced prepared food, and think that's it.

Come at 7 AM on a Tuesday instead. The market is entirely different: vendors setting up, chefs from restaurants shopping for fresh ingredients, locals buying their weekly vegetables. The Naschmarkt stretches for a kilometer, and the farther you walk from Karlsplatz, the more authentic it becomes.

Skip the restaurants and focus on the vendors. There are Turkish spice merchants, Persian shops selling saffron and pistachios, Polish delis with pickled everything, Vietnamese grocers, Greek olive stands, Austrian farmers selling seasonal produce. This is where Vienna's diversity actually lives—not in tourist brochures but in the daily commerce of food.

Buy breakfast from vendors: a Leberkäse semmel (a very Viennese meatloaf sandwich), fresh börek from a Turkish stand, or a paper cone of olives and cheese from one of the Mediterranean shops. Eat standing up or sitting on the curb. This is Vienna eating like Viennese, not tourists.

Then walk to the Saturday flea market at the Naschmarkt's western end (only on Saturdays). Dig through piles of Habsburg-era porcelain, vintage clothing, old cameras, Communist memorabilia from Vienna's time as an occupied city, Art Nouveau jewelry, dusty books in German. The junk is real, prices are negotiable, and you'll find things that tell Vienna's complicated 20th-century story—occupation, division, refugees, reconstruction.

The Danube Nobody Swims In

The "Blue Danube" of Strauss waltzes? It's brown, channelized, and mostly industrial. The Danube Canal that cuts through the city? Covered in graffiti, lined with concrete, bordered by bike paths and beach bars.

And it's wonderful.

In summer, the Danube Canal transforms into Vienna's unofficial beach. Locals spread towels on the concrete banks, dangle their feet in the water (it's clean enough), drink beer from Tel Aviv Beach or Strandbar Herrmann, and pretend they're on vacation without leaving the city. The atmosphere is relaxed, unpretentious, and distinctly un-imperial.

Rent a bike and ride the entire Danube path—from the city center out to the Donauinsel (Danube Island), a 21-kilometer artificial island created for flood control that's now Vienna's massive recreational park. On weekends, it's packed with families grilling, cyclists, runners, people swimming in the Neue Donau (New Danube), teenagers drinking on the banks, nudists at designated areas (yes, really—Austria is very comfortable with public nudity).

This is Vienna relaxing—not in chandeliered cafés but in swim trunks and bikinis, eating grilled sausages, blasting music from portable speakers, thoroughly informal.

The Danauinsel also hosts the massive Donauinselfest every June—Europe's largest free open-air festival with three million attendees, multiple stages, and zero pretension. It's chaotic, crowded, democratic, and utterly unlike the Vienna that tourists imagine. Go. It's possibly the most Viennese thing you can do.

Master the Beisl

Forget fancy restaurants. The soul of Viennese cuisine lives in Beisln (plural of Beisl)—working-class taverns serving traditional food without fuss or excessive prices.

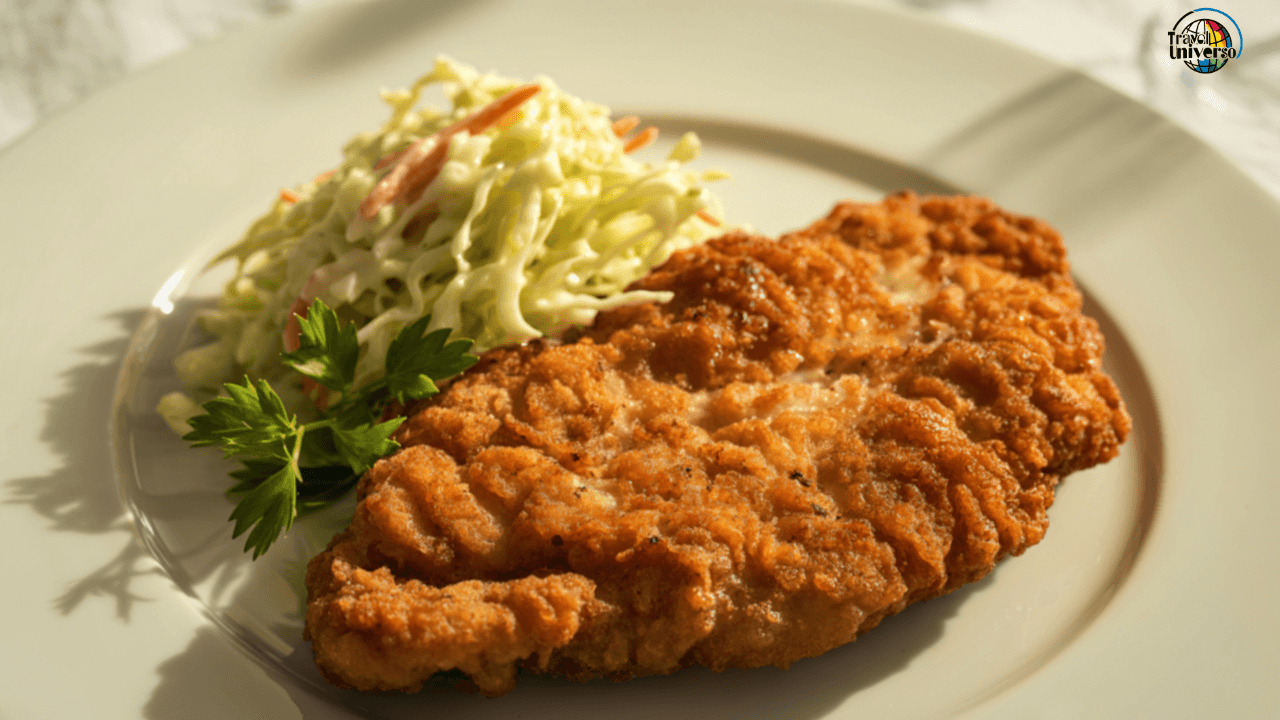

A proper Beisl has mismatched furniture, nicotine-stained walls (even post-smoking-ban), surly-but-secretly-kind servers, and a menu that hasn't changed in 50 years: Wiener Schnitzel (real veal, pounded thin, breadcrumb-crusted, the size of a plate), Tafelspitz (boiled beef that Emperor Franz Joseph ate daily), Gulasch, Schweinsbraten (roast pork), and Grammelpogatscherl (a kind of savory pastry with cracklings).

Try Gasthaus Pöschl in Josefstadt, Reinthaler's Beisl near Stephansplatz, or Zum Schwarzen Kameel (which looks fancy but functions as a Beisl). Order a Krügerl (half-liter) of Austrian beer—Ottakringer, Stiegl, or Gösser. The food is heavy, meaty, designed for workers who needed calories. It's not subtle, but it's deeply satisfying.

Pay attention to the sides: Austrian potato salad (made with broth, not mayo), cucumber salad (sweet-sour), Semmelknödel (bread dumplings), Erdäpfelpüree (mashed potatoes made with enough butter to constitute a cardiovascular event). This is Viennese comfort food, and it pairs perfectly with beer and conversation.

The unspoken Beisl rule: you're there to eat and drink slowly. Americans in particular struggle with this—we want to order, eat, pay, leave. Austrians linger. The meal is two hours minimum. Your waiter might seem disinterested; this isn't bad service, it's respect for your space. Wave when you need something. When you're ready to pay, ask for "Die Rechnung, bitte."

The Lesson Vienna Teaches

If Istanbul teaches keyif and Thailand teaches sanuk, Vienna teaches something harder to embrace: Weltschmerz—"world-weariness," the recognition that the world will never match our ideals, that empires fall, that beauty is inseparable from decay, that pleasure and melancholy are married to each other.

Vienna has been dying magnificently for over a century. The empire collapsed in 1918. The city spent the 20th century occupied, divided, bombed, rebuilt, diminished from capital of 50 million to capital of 8 million. And yet it persists—not by denying loss but by incorporating it into daily life, by sitting in those coffeehouses thinking long thoughts, by maintaining traditions precisely because they're old, by building radical social housing alongside Baroque palaces, by treating culture not as tourism but as civic necessity.

You can't understand Vienna from a hop-on-hop-off bus. You understand it by sitting in a Heuriger until dark, by riding your bike along the industrial Danube, by spending three hours in a coffeehouse doing nothing, by exploring workers' palaces and Communist monuments, by eating cheap sausages under U-Bahn bridges, by recognizing that a city can be simultaneously grand and humble, imperial and socialist, formal and irreverent.

The Vienna in the guidebooks is real. But the Vienna that sits in the courtyards of Gemeindebauten drinking wine from the surrounding hills, that swims in the concrete Danube Canal on summer evenings, that eats Käsekrainer at 2 AM, that spends Sunday afternoons alone with a book in a smoky café—that Vienna is true.

And it's been waiting there all along, just beyond the palace gates, in the hills where vines grow, in the places where Viennese actually live their beautifully melancholic, stubbornly egalitarian, quietly radical lives.

Get our travel tips, itineraries and guides by email

Sign up for my newsletter!

Name

Let us know what you think in the comments!

Newsletter

Subscribe to the newsletter and stay in the loop! By joining, you acknowledge that you'll receive our newsletter and can opt-out anytime hassle-free.

© 2026 Travel Universo. All rights reserved.