Scotland Beyond the Postcards: Mist, Myth, and the Art of the Long Dark

Scotland markets itself with Highland cows, tartan, and misty glens—romantic shorthand for a country that's far stranger, darker, and more compelling than the tourism posters suggest. This is a land shaped by volcanic violence and glacial patience, by clan warfare and Calvinist severity, by oil money and post-industrial decline, by a language nearly erased and a culture that refuses to die.

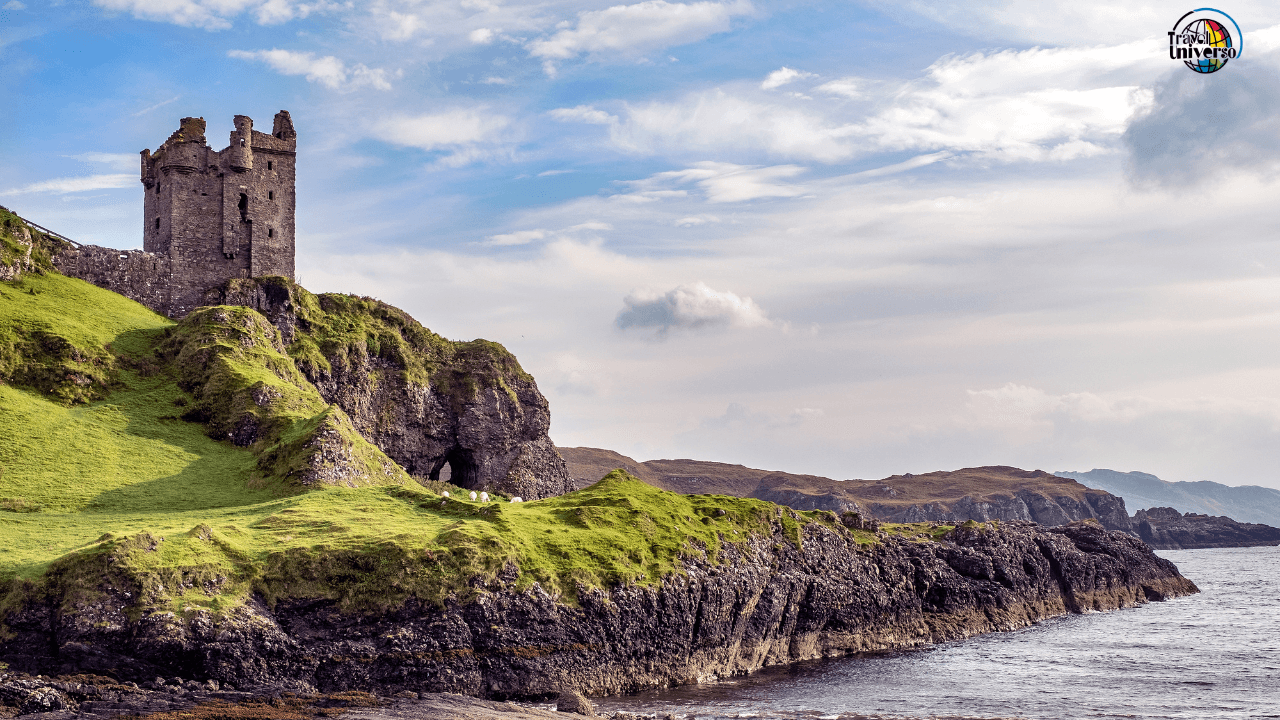

Most visitors hit Edinburgh's Royal Mile, pose at a castle, drive through the Highlands snapping photos, and leave thinking they've seen Scotland. But the real Scotland—the one that still haunts its inhabitants—reveals itself slowly, reluctantly, usually in bad weather, often in the spaces between what guidebooks mention.

This is a country that teaches you to find beauty in bleakness, community in harshness, and humor in the face of historical catastrophe. And you won't find it by chasing Braveheart fantasies.

The Bothy Culture: Scotland's Open Secret

Deep in the Highlands, far from roads and tourists, sit hundreds of stone bothies—basic mountain shelters maintained by volunteers for free use by anyone. No booking, no payment, no amenities beyond four walls and maybe a fireplace. They're scattered across some of Britain's most remote landscapes: Cape Wrath, the Cairngorms, the wild west coast, the islands.

This is where you find Scotland's soul.

Reaching a bothy requires commitment. You hike for hours—sometimes a full day—carrying everything you need: sleeping bag, food, fuel, whisky (obviously). The bothies themselves are spartan: stone walls, wooden sleeping platforms, a visitor's book filled with entries from decades of wanderers. No electricity, no running water, no phone signal. Just you, the landscape, and whoever else arrives seeking shelter.

Start with something accessible: the Schoolhouse Bothy near Loch Ossian, reachable by a few hours' walk from Corrour Station (Britain's most remote train station, itself worth the journey). Or Shenavall in Wester Ross, beneath the towering peaks of An Teallach, requiring a five-mile walk through empty glen.

The bothy culture operates on an honor system: leave the place cleaner than you found it, carry out all rubbish, share supplies if someone arrives unprepared, contribute firewood if you use the fireplace. It's a practical socialism born from necessity—when you're 10 miles from civilization in horizontal rain, class distinctions dissolve quickly.

Spend a night in a bothy during a storm. Listen to wind testing the roof slates. Watch weather systems roll through the glen outside. Share whisky with the German cyclist and the Scottish fisherman who arrived separately but now huddle around the same fire. Read the bothy book entries: poems, drawings, accounts of storms survived, memorials to friends who loved this place.

This is Scotland stripped of romantic nonsense—just landscape, weather, and the people stubborn enough to be there.

Drink in a Scheme (and Learn What That Means)

"The Schemes" is Scottish slang for council housing estates—the equivalent of housing projects—built from the 1950s onward to house Glasgow's working class when tenements were cleared. They're often rough, sometimes grim, always authentic, and completely absent from tourist itineraries.

But understanding Scotland without understanding the Schemes is like understanding Vienna without seeing the Gemeindebauten—you're missing half the story.

Take a bus to Easterhouse or Drumchapel in Glasgow's outskirts. These aren't tourist destinations; they're functioning communities where people live, often in poverty but also with fierce local pride. The architecture is brutal 1960s Modernism—high-rises and low-rises in concrete, designed with utopian ideals that often failed in practice.

Find a local pub. Not a gastropub, not a craft beer bar—a proper working men's pub with sticky floors, fruit machines, and regulars who've been drinking there for 40 years. Order a pint of Tennent's. Strike up a conversation. Glaswegians, especially after a pint, are among the friendliest, funniest, most loquacious people on earth.

Yes, the accent is nearly impenetrable at first. Yes, they swear constantly (swearing in Scots is practically punctuation). Yes, they'll take the piss out of you mercilessly. But they'll also tell you stories—about shipbuilding's collapse, about Thatcher's destruction of Scottish industry, about surviving on grit and humor when everything else was taken away.

This is where you learn that Scottish identity isn't about tartans and bagpipes—it's about class, about survival, about finding dignity in hardship. The Schemes produced Scotland's best writers (Irvine Welsh, James Kelman), musicians, and poets. They're also sites of genuine community solidarity in a way that middle-class suburbs rarely achieve.

Don't romanticize poverty. But don't ignore where most Scots actually lived and still live. The country's working-class history—from Highland Clearances to shipyard closings—explains Scotland's politics, its independence movement, its complicated relationship with England, and its stubborn egalitarianism more than any castle ever will.

The Island Sabbath

Take the ferry to the Outer Hebrides—Lewis and Harris, North and South Uist, Barra—and you enter a different Scotland entirely. Gaelic is still spoken. Presbyterianism still dominates. And on Sunday, everything stops.

The Hebridean Sabbath isn't a quaint tradition—it's a lived reality. On Lewis, the ferry doesn't run on Sunday. Shops close. Playgrounds are chained shut. Pubs don't serve alcohol. Even hanging laundry outside is frowned upon. You're expected to observe the Sabbath whether you're religious or not, and locals take it seriously.

This might sound oppressive—and many young Hebrideans chafe against it—but it also creates something increasingly rare: a day of enforced rest, of genuine quiet, where the entire community shares the same rhythm.

Arrive on a Saturday. Stock up on food and whisky (seriously—shops and off-licenses close tight on Sunday). On Sunday morning, you have two choices: attend church or walk.

The churches—Free Church, Free Presbyterian—hold services in Gaelic with psalm singing that's haunting and severe: unaccompanied, unharmonized, utterly unlike any church music you've heard. Even if you're not religious, the cultural experience is profound. These people are singing in a language the British government once tried to erase, maintaining traditions centuries old, in remote islands that survive through sheer stubbornness.

Or walk. Sunday in the Hebrides means empty roads, silent villages, and landscapes so vast and lonely they feel prehistoric. Walk to standing stones at Callanish—older than Stonehenge, arranged in a Celtic cross pattern that predates Christianity by millennia. Walk the beaches at Luskentyre—white sand, turquoise water, mountains beyond, not a soul in sight. Walk the moorlands where peat is still cut by hand, where crofts scatter across hills like dropped seeds.

The Sabbath silence isn't absence—it's presence. It's the sound of wind, of waves, of birds. It's space to think without distraction. It's the landscape asserting itself, reminding you that humans here are temporary, that the islands have their own time.

By Monday, you'll understand why this weekly pause persists: it's not about religious control but about maintaining boundaries—between work and rest, between human noise and natural silence, between the modern world's constant demands and something older and more essential.

Eat a Munchy Box at 2 AM

Scottish cuisine has a terrible reputation—deep-fried Mars bars get all the press. But Scotland's actual food culture is weirder and more wonderful than outsiders realize, and the pinnacle of this is the Munchy Box.

Picture a pizza box. Now fill it with everything from a Scottish takeaway: pakora, chicken tikka, pizza slices, kebab meat, chicken nuggets, naan bread, chips (fries), onion rings, garlic bread, sometimes even a burger. It's designed to feed three people but is routinely consumed by one drunk person at 2 AM.

The Munchy Box is Scottish-Pakistani fusion born from Glasgow's substantial South Asian community and Scotland's drinking culture. It's beautiful chaos—the culinary equivalent of Scottish identity itself, which borrows, adapts, and creates something distinctly its own.

Find a proper takeaway in Glasgow or Edinburgh—preferably one recommended by locals, open late. Order a Munchy Box around closing time on a Friday or Saturday. Observe the theater: drunk Scots negotiating their orders, takeaway staff who've seen everything, the choreography of late-night hunger and alcohol.

Or better yet: experience the Scottish "carry-out" culture properly. Buy alcohol from an off-license (liquor store), bring it to a friend's flat, and when hunger strikes at midnight, send someone for a Munchy Box. This is how Scots socialize—not in expensive bars but in living rooms, with cheap alcohol and cheaper food, talking until dawn.

While you're at it, try the actually good Scottish food: proper fish and chips wrapped in paper, eaten on a windy pier. A Scotch pie from a football match—greasy, meaty, perfect. Cullen skink (smoked haddock soup) in a fishing village. Black pudding for breakfast. Tattie scones. A proper Scottish breakfast with Lorne sausage (square sausage—only in Scotland). Stovies—a simple dish of potatoes, onions, and leftover meat that tastes like Scottish comfort food incarnate.

And yes, haggis. But not at a touristy Burns Supper—order it at a regular restaurant as a starter. It's actually delicious: savory, peppery, rich. The sheep's stomach thing is just packaging.

Walk Glasgow's Necropolis at Dusk

Edinburgh gets all the tourist attention, but Glasgow—Scotland's largest city—is rawer, funnier, friendlier, and more itself. And its most atmospheric spot isn't a castle but a graveyard.

The Glasgow Necropolis rises on a hill above the cathedral—a Victorian garden cemetery with 50,000 burials and monuments ranging from austere Celtic crosses to Egyptian-revival mausoleums. It's Glasgow's personality in stone: dramatic, morbid, darkly beautiful, and laced with dark humor.

Visit at dusk. Enter through the Bridge of Sighs. Wander the paths as light fades and the city spreads below you—cranes, church spires, tenements, tower blocks. Read the gravestones: cholera victims from the 1832 epidemic, tobacco merchants who made fortunes from empire, architects who designed the city, ordinary workers with extraordinary epitaphs.

At the summit sits the monument to John Knox, the Protestant reformer whose severe Calvinism still haunts Scottish culture. From here, you can see everything: Victorian Glasgow's wealth, modern Glasgow's struggles, the Campsie Fells beyond, the River Clyde below.

The Necropolis is a perfect metaphor for Scotland: beautiful but melancholic, proud but aware of mortality, shaped by religious severity and working-class grit, obsessed with its own history, impossible to understand without confronting death and decline.

As darkness falls, head down to the city center. Glasgow at night reveals its true character: pub culture spilling onto streets, live music in a hundred venues, late-night chip shops, drunk people singing, street preachers shouting, students and shipyard workers and artists all mixing, a city that drinks hard and laughs harder because the alternative—given the history, the weather, the economic hardship—is unbearable.

The Cèilidh: Organized Chaos

Every Scottish celebration ends the same way: a cèilidh (pronounced "KAY-lee")—a social gathering with traditional music and dancing. Tourists encounter staged cèilidhs at hotels. But a real cèilidh—at a wedding, a community hall, a pub's back room—is something else entirely.

The music is live: fiddles, accordions, sometimes bagpipes, always fast and driving. The dances have names like Strip the Willow, Dashing White Sergeant, Gay Gordons. A caller shouts instructions over the music. Dancers—drunk, sober, young, old, coordinated, hopeless—careen around the floor in organized pandemonium.

You will be pulled into a cèilidh if you're anywhere near one. Protestations that you don't know the dances are irrelevant—nobody does, and everyone muddles through anyway. The point isn't precision; it's participation, sweat, laughter, and community.

Find a cèilidh at a local venue—check what's happening in village halls, particularly in the Highlands and Islands. Tickets are usually cheap. Dress casual (you'll be sweating). Bring stamina and willingness to look foolish.

What makes a cèilidh distinctly Scottish: it's egalitarian (everyone dances with everyone), chaotic (mistakes are expected and hilarious), energetic (it's basically cardio with fiddles), and communal (you're never dancing alone—you're always partnered, linked, or grouped). It's the opposite of the formal, hierarchical Scotland of tartans and ceremony—this is Scotland as it actually socializes, breaking down barriers through shared exhaustion and laughter.

After several hours, when the last song ends and everyone's drenched in sweat, you'll understand something essential about Scottish culture: it's not about romantic individualism but about collective survival, about finding joy in community because the landscape, the history, and the weather all demand resilience.

The Lesson Scotland Teaches

If Vienna teaches Weltschmerz and Thailand teaches sanuk, Scotland teaches something harder to name—perhaps it's best described in Scots: "thrawn." It means stubbornly contrary, persistently resistant, unbreakable even when broken.

Scotland is thrawn. It's a country repeatedly conquered, culturally suppressed, economically exploited, whose language was nearly erased, whose people were cleared from their land to make room for sheep, whose industries collapsed, whose weather is objectively terrible. And yet it persists—not through denial but through dark humor, fierce community, and a refusal to pretend things are fine when they're not.

You learn this by walking in horizontal rain to a remote bothy. By drinking in Scheme pubs where people have every reason to be bitter but choose laughter instead. By observing a Sabbath silence that insists on boundaries in a world with none. By sharing a Munchy Box with strangers at 2 AM. By careening around a cèilidh floor with everyone from teenagers to pensioners, all equally sweaty and ridiculous and joyful.

The Scotland in the guidebooks—castles and bagpipes and Highland romance—is a Victorian invention, created after the real Highland culture was destroyed. It's pretty, profitable, and mostly false.

The real Scotland is harsher, funnier, more working-class, more complicated. It's a country that produces world-class whisky and terrible weather, stunning landscapes and brutal housing estates, warm hospitality and violent history. It's a place where you learn that beauty and bleakness aren't opposites but companions, that community matters more than comfort, and that sometimes the most radical act is simply persisting—with humor, with dignity, with thrawn stubbornness—when everything says you shouldn't.

And you'll find that Scotland, just beyond the postcards and tartan tat, in the bothies and the Schemes and the Hebridean silence, in the Necropolis and the cèilidhs and the late-night takeaways, waiting for those willing to see it as it actually is: dark, funny, proud, scarred, and utterly unbreakable.

Get our travel tips, itineraries and guides by email

Sign up for my newsletter!

Name

Let us know what you think in the comments!

Newsletter

Subscribe to the newsletter and stay in the loop! By joining, you acknowledge that you'll receive our newsletter and can opt-out anytime hassle-free.

© 2026 Travel Universo. All rights reserved.