Quebec City's Beautiful Defiance: Winter, Memory, and the Art of Refusing to Disappear

Quebec City announces itself through contradiction. It's a walled fortress city in North America—the only one north of Mexico. It's French but not France, Canadian but barely, North American but European in soul. It survives seven months of brutal winter with a collective shrug and a festival celebrating ice. It's a UNESCO World Heritage site that's also a working city of 540,000 people, where the cobblestoned tourist core is surrounded by sprawling suburbs, strip malls, and Tim Hortons like anywhere else in Canada.

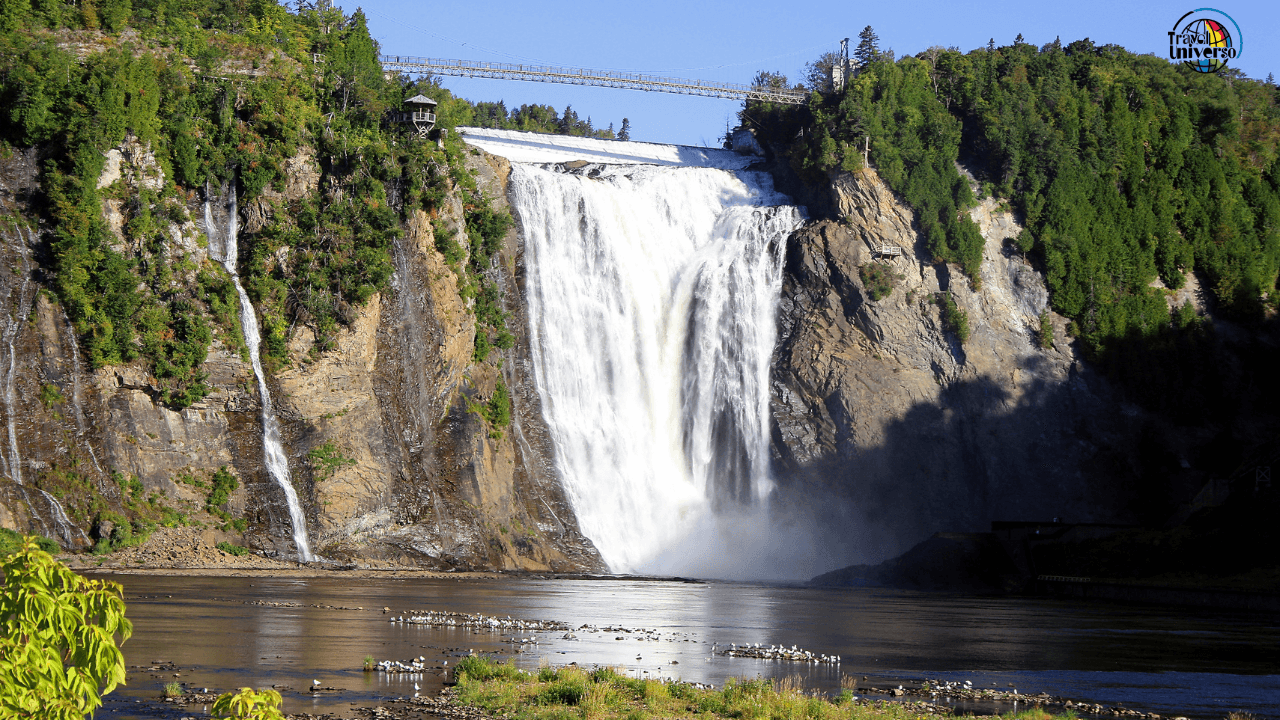

Most visitors see Château Frontenac, walk the old city's ramparts, maybe visit Montmorency Falls, eat poutine, and leave thinking they've glimpsed French Canada. They've actually seen a carefully preserved stage set—beautiful, genuine in its way, but missing the point entirely.

The real Quebec City—the one that shaped Québécois identity, that maintains French language and culture in an Anglophone continent through sheer stubbornness, that turns winter from obstacle into identity, that carries 400 years of siege mentality and colonial resentment—exists in the neighborhoods beyond the walls, in the winter darkness, in the language itself, in the daily defiance of simply continuing to exist as something distinct.

This is a city that teaches you that survival can be an act of resistance, that cold is something you don't fight but inhabit, and that maintaining difference requires conscious effort every single day.

Survive Carnival in February

Everyone knows Quebec has winter. Few understand what that means: five months where temperatures regularly hit -20°C (-4°F), where snowbanks reach second-story windows, where the river half-freezes despite its massive size, where going outside unprepared can literally kill you within hours.

Most cities endure winter. Quebec celebrates it with Carnaval de Québec—the world's largest winter festival, held in February, the coldest, most miserable month, precisely when seasonal depression peaks.

But here's what tourists miss: Carnaval isn't quaint folk tradition—it's collective psychological warfare against winter's darkness. It's Québécois culture saying: if we must live through this, we'll make it magnificent.

Skip the official events (parades, ice palace, Bonhomme—the creepy snowman mascot). Instead, experience Carnaval as locals do: by drinking caribou (a traditional mixture of red wine, whisky, and maple syrup) from a hollow plastic cane while standing outside in -25°C, then stumbling to house parties in Saint-Roch or Saint-Jean-Baptiste, where entire neighborhoods open their doors, blast music, and drink until the cold becomes irrelevant.

The caribou tradition is essential—it's antifreeze masquerading as cultural practice. You need alcohol to tolerate standing outside for hours. The plastic cane lets you carry it everywhere. The sweetness masks how much you're drinking. By 11 PM, the entire city is pleasantly buzzed, dancing outside in parkas, proving that humans can make anything tolerable through ritual and intoxication.

Walk through the neighborhoods during Carnaval. Houses are decorated with colored lights, snow sculptures appear in front yards, groups of friends move from party to party. The temperature is murderous but everyone's outside anyway, because staying inside means winter wins.

This is when you understand: Québécois identity is inseparable from winter. Toronto and Montreal complain about cold. Quebec City accepts it as foundational—you don't live here despite winter but because of it, because the cold weeds out the uncommitted, because surviving seven months of darkness and snow creates solidarity that summer people will never understand.

Speak French (Badly) or Don't Speak At All

Quebec City is 95% Francophone. Not "bilingual with French flavor" like Montreal—actually, functionally, defiantly French. Signs are in French. Menus are in French. Conversations are in French. Government operates in French. The radio plays French music. Life happens in French, and English exists grudgingly, as a concession to tourists and federal requirements.

This isn't quaint. It's political.

Speaking French in Quebec City—even badly—changes everything. Attempt "Bonjour, je voudrais..." before switching to English, and you'll see faces soften. Start in English, and you'll get service, but it'll be curt, minimal, a transaction rather than an interaction.

The language issue is Quebec City's defining tension. This is a French city conquered by the British in 1759, absorbed into British North America, then Canadian Confederation, surrounded by 350 million Anglophones. Speaking French isn't just communication—it's cultural survival, an act of resistance repeated millions of times daily.

The Québécois accent is its own thing—not Parisian French but descended from 17th-century Norman and regional dialects, evolved in isolation for 250 years, with its own vocabulary, expressions, and sounds. French visitors often struggle to understand it. That's fine—it's not for them. It's Quebec's French, shaped by this place, this climate, this history.

Learn basic phrases: "Bonjour, comment ça va?" (Hello, how are you?), "Merci, bonne journée" (Thanks, have a good day), "Excusez-moi, je ne parle pas bien français" (Sorry, I don't speak French well). Use them sincerely, not performatively. You're acknowledging that you're a guest in a French city, that their language matters, that assimilation isn't inevitable.

Visit neighborhoods where tourists never go: Limoilou, Vanier, Charlesbourg. Here, you'll find zero English, pure working-class Québécois life—dépanneurs (corner stores) selling cigarettes and lottery tickets, rôtisseries selling poulet BBQ, tavernes (working-class bars), church spires still dominating skylines even as Quebec has become North America's most secular society.

The language question reveals Quebec's existential anxiety: can French survive here? Each generation worries it's the last. The birthrate dropped. Immigration brings non-Francophones. English dominates globally. And yet French persists—through language laws (Bill 101), through institutional support, through daily practice, through collective will.

Speaking French in Quebec City isn't about being polite to locals—it's about acknowledging a 250-year struggle to maintain linguistic and cultural difference against overwhelming pressure to assimilate. Your bad French matters more than you think.

Walk the Plains of Abraham in November

The Plains of Abraham—now Parc des Champs-de-Bataille—is where Quebec fell to the British in 1759. A 20-minute battle between General Wolfe's British forces and General Montcalm's French forces decided North American history: Britain won, France lost, Quebec became British, and 260+ years of resentment began.

Every tourist visits in summer when the park is green and pleasant. Visit instead in November—after leaves fall, before snow, when the city is gray, wet, cold, and empty. Walk across the battlefield at dusk as darkness comes early (4:30 PM in November).

The Plains are vast, flat, exposed to wind off the river. Imagine September 13, 1759: thousands of soldiers fighting in the pre-dawn darkness, both generals dying (Wolfe victorious, Montcalm defeated), Quebec's fate sealed. The battle lasted barely 15 minutes but shaped everything that followed.

Walk to the Musée National des Beaux-Arts and the Martello towers. These defensive structures were built later, expecting American invasion (which came in 1775 and failed). Quebec has spent centuries anticipating attack, actual or cultural.

Stand at the cliff edge overlooking the St. Lawrence. The river is massive here—more sea than river, tidal, powerful. This geography made Quebec City strategic: control this point, control river access to the continent's interior. The Citadel—still an active military installation—looms behind you, British-built to defend against Americans, now home to a French-Canadian regiment. The ironies are thick.

The Plains teach Quebec's foundational trauma: military defeat, colonial subjugation, survival as a conquered people.

The British won but never assimilated Quebec—Catholicism and French language were protected (Quebec Act 1774) because suppression risked rebellion. So Quebec remained French, Catholic, distinct—a nation within a nation, conquered but unbroken.

Modern Quebec City sits atop this history. The Quiet Revolution (1960s) secularized society—churches emptied, birthrates plummeted, nationalist politics emerged. Two referendums on independence (1980, 1995) failed narrowly. Sovereignty remains debated. The question persists: what is Quebec? A province? A nation? Something undefined, existing in the space between?

November on the Plains—cold, dark, empty—feels appropriate for contemplating this. Quebec's history isn't triumphant; it's about endurance despite defeat, maintaining identity against pressure, surviving culturally when military survival failed.

Eat at a Casse-Croûte and Understand Comfort

Forget the fancy restaurants in Vieux-Québec serving haute cuisine to tourists. Quebec's soul food lives in casse-croûtes—casual counter-service restaurants serving Québécois classics to families and workers.

Find Chez Ashton, Snack Bar Saint-Jean, or any neighborhood casse-croûte in Limoilou or Beauport. Order poutine—the real kind, with fresh cheese curds that squeak, thick brown gravy, crispy fries. This isn't gourmet poutine with duck confit and truffle oil—it's working-class comfort food, cheap, filling, delicious.

But also try the rest of Quebec's specific food culture: tourtière (meat pie, especially at Christmas), pâté chinois (Quebec's shepherd's pie), cretons (pork pâté), fèves au lard (baked beans), ragout de boulettes (meatball stew), and pea soup thick enough to stand a spoon in.

The casse-croûte also serves steamés—steamed hot dogs in soft buns with chopped onions, mustard, relish, coleslaw. They're unlike American hot dogs—smaller, steamed not grilled, assembled with specific toppings in specific order. Every casse-croûte has its own method. Arguments about the "correct" way are endless.

For breakfast, try cabane à sucre food (sugar shack traditions): oreilles de crisse (fried pork rinds), jambon à l'érable (maple-glazed ham), baked beans in maple syrup, tire sur la neige (maple taffy on snow—only in late winter/early spring).

This food reflects Quebec's history: poor, rural, cold, Catholic. Meals needed to be filling, cheap, capable of feeding large families. Nothing is subtle; everything is hearty, sweet or savory to extremes, designed for physical labor and brutal winters.

The casse-croûte culture also shows class distinctions. Middle-class Quebec City eats at bistros and gastropubs. Working-class Quebec eats at casse-croûtes, tavernes, and rôtisseries. The food marks identity—eating at Ashton signals you're unpretentious, local, authentic. Eating at fancy Vieux-Québec restaurants signals you're a tourist or out-of-touch.

Order in French, even badly. Sit at the counter. Observe families, construction workers, elderly regulars. This is daily life—unglamorous, genuine, the Quebec that exists beyond postcards.

Ride the Ferry to Lévis in January

The Quebec-Lévis ferry crosses the St. Lawrence year-round, 15 minutes each way, often through ice floes in winter. It costs $3.70. Locals use it for commuting. Tourists take it for the view.

Take it in January, at sunset (which happens around 4:30 PM). Board in the Vieux-Port. Stand outside on deck despite the cold—the views require it.

As the ferry crosses, Quebec City unfolds: Château Frontenac dominating the skyline, the Citadel on the cliff, church spires, the Old City's lights beginning to glow. Ice floats in the river—massive chunks grinding against the ferry's hull. The cold is shocking—wind off the river cuts through every layer. Your face hurts within minutes.

But here's the revelation: the view from the water shows Quebec City as it actually is—a fortress on a cliff, strategically positioned, defensible, beautiful but harsh, shaped entirely by geography and military necessity. From this angle, the city's purpose is obvious: control the river, survive siege, endure.

Cross to Lévis. Disembark briefly. Walk to the terrace for the opposite view. From here, Quebec City looks like a European capital transplanted impossibly to North America—utterly incongruous, defiantly anachronistic, a French city that refused to disappear despite every historical pressure.

Return on the next ferry. By now, darkness has fully fallen, the city glows against black sky and black water, and you're standing in -20°C wind understanding why Québécois are the way they are: if you can handle this, you can handle anything. The cold, the darkness, the isolation—it forges identity, creates solidarity, separates those who belong from those who don't.

The ferry is also where you'll see everyday Quebec City: commuters reading Le Soleil (the local French paper), students, workers, families. Nobody's performing Frenchness or Québécois identity—they're just living it, crossing the river like their ancestors did (by canoe, then by ice bridge, now by ferry), maintaining routines despite cold that would paralyze warmer cities.

Discover Saint-Roch's Resurrection

Saint-Roch—the neighborhood just outside the Old City walls—was Quebec City's working-class heart: factories, workers' housing, parish churches, tavernes. Post-war, it declined: deindustrialization, poverty, empty storefronts. By the 1980s-90s, it was Quebec City's roughest area—drugs, prostitution, urban decay.

Now it's hipster central: microbreweries, coffee shops, vintage stores, artists' studios, young professionals. It's gentrification, but Québécois-style—less aggressive than American cities, more concerned with maintaining French character, still authentically working-class in parts.

Walk Rue Saint-Joseph, the main commercial street. It's covered by a controversial glass canopy (added in the failed 1990s revitalization attempt, now a quirky feature). You'll find Le Cercle (concert venue and bar), La Barberie (cooperative brewery—very Quebec), multiple vintage shops, Vietnamese restaurants (Quebec City has a substantial Vietnamese community), and just... normal life. People shopping, working, living.

Saint-Roch shows Quebec City's other face: not historic preservation but contemporary evolution, struggling with the same issues as everywhere—how to revitalize without displacing, how to attract investment without losing character, how to remain affordable.

Visit Les Halles de Cartier, an indoor public market. It's smaller than Montreal's markets but more authentically local—cheese vendors, butchers, bakers, produce sellers, locals shopping for dinner. Buy bread from a boulangerie, Quebec cheese (try Le Riopelle or any raw milk cheese—Quebec has excellent cheese culture), charcuterie.

Then walk to the edges of Saint-Roch where gentrification hasn't reached. You'll find older Quebec: working-class housing, corner dépanneurs, tavernes, churches now converted to condos, the bones of industrial Quebec still visible.

Saint-Roch is where young Québécois live—artists, musicians, students, service workers. They can't afford Vieux-Québec (too touristy, too expensive), and they reject Anglo Montreal (Quebec City is more intensely Québécois, more politically nationalist). Saint-Roch is their neighborhood: French, creative, affordable-ish, distinctly local.

Spend an evening here: drink at a microbrasserie (Quebec has exceptional craft beer culture), eat Vietnamese pho (Quebec's comfort food alongside poutine), catch live music, observe young Quebec negotiating modernity while maintaining difference. This is the Quebec that will determine whether French culture survives another generation.

The Lesson Quebec City Teaches

If Ireland teaches endurance and Mexico City teaches thriving in chaos, Quebec City teaches something more specific and more defiant: the art of maintaining difference through sheer will, of refusing to disappear even when assimilation would be easier, of turning isolation and hardship into identity.

Quebec City exists in a state of permanent resistance. It resists English, resists Canadian homogeneity, resists winter, resists modernity's pressure toward sameness. Every generation worries it's the last to be truly French, truly Québécois, truly distinct. And every generation persists anyway.

This creates a particular mentality: proud but defensive, welcoming but suspicious, open but protective, confident in cultural superiority while anxious about cultural survival. It's exhausting, this constant vigilance, this daily decision to remain French in an Anglophone continent. But it's also exhilarating—every conversation in French, every child raised bilingual, every winter survived is a small victory.

You feel this in the language politics, in Carnaval's defiant celebration of winter, on the Plains where defeat still resonates, in the casse-croûtes serving food that proclaims identity, on the ferry crossing the river that defines everything, in Saint-Roch where young people build a future that's distinct but uncertain.

The Quebec City in guidebooks—Château Frontenac, narrow cobblestoned streets, quaint European charm—is real but incomplete. The real Quebec City is the February darkness and caribou-fueled parties, the French language as daily practice and political statement, the working-class neighborhoods maintaining identity through food and family, the constant negotiation between preservation and evolution, the stubborn insistence on being French in America not despite the difficulty but because of it.

It's a city that shouldn't exist—a French-speaking fortress in North America, clinging to language and culture 260 years after military defeat, surviving through winters that would break weaker places, maintaining difference when globalization demands homogeneity.

And yet it endures—beautifully, defiantly, stubbornly, impossibly—teaching anyone who pays attention that survival itself can be revolutionary, that culture is something you practice daily or lose forever, and that the cold, the isolation, the constant struggle aren't obstacles to identity but its very foundation.

Bonne journée. Restez au chaud. (Have a good day. Stay warm.)

Get our travel tips, itineraries and guides by email

Sign up for my newsletter!

Name

Let us know what you think in the comments!

Newsletter

Subscribe to the newsletter and stay in the loop! By joining, you acknowledge that you'll receive our newsletter and can opt-out anytime hassle-free.

© 2026 Travel Universo. All rights reserved.