Ireland Beyond the Craic: Rain, Ghosts, and the Eloquence of Silence

Ireland sells itself on leprechauns, Guinness, and the craic—that untranslatable concept of good times, conversation, and conviviality. Tour buses ferry visitors from the Cliffs of Moher to the Ring of Kerry to Temple Bar, where American students drink green beer and sing "Galway Girl" with people who aren't actually from Galway.

But Ireland—the real Ireland that shaped Joyce, Beckett, and Heaney—is far stranger and darker than the tourist board admits. This is a country haunted by famine ghosts and civil war bitterness, where Catholicism's grip is finally loosening after decades of scandals, where a thousand years of colonization created a complicated relationship with identity, language, and power. It's also shockingly modern—a tech hub, a tax haven, a place where Google and Facebook have European headquarters, where a generation has grown wealthy in ways their grandparents couldn't imagine.

The Ireland that matters exists in the spaces between: in the bogs that still yield Bronze Age bodies, in the Gaeltacht villages where Irish is the first language, in the housing estates ringing Dublin and Cork, in the rural pubs on Tuesday afternoons, in the weather that shapes everything—the horizontal rain, the sudden sun, the forty shades of green that actually exist when clouds break just right.

This is a country that teaches you the difference between loneliness and solitude, between talking and saying something, between sentiment and sentimentality. And you won't find it by kissing the Blarney Stone.

Walk the Bogs Alone

Ireland is one-sixth bogland—vast expanses of peat, heather, and cotton grass stretching across the Midlands, the West, the mountain slopes. Bogs seem empty, monotonous, forgettable. They're actually Ireland's memory banks, preserving everything: 4,000-year-old butter, Bronze Age trackways, Iron Age bodies tanned and pickled, centuries of pollen recording climate shifts, bones of extinct Irish elk.

But more than that, bogs are where you encounter Irish solitude—not the performative loneliness of sad songs but something older and stranger.

Take a bus to the Midlands—Offaly, Laois, Westmeath—regions tourists ignore entirely. Find Clara Bog or Raheenmore Bog. These are raised bogs, domed slightly from centuries of peat accumulation, with boardwalks threading through. Go on a weekday. You'll be alone.

Walk. The landscape is alien: sphagnum moss in impossible colors (red, green, gold), pools of dark water reflecting gray sky, carnivorous sundew plants glistening, the occasional stunted pine twisted by wind and poor soil. The silence is absolute—no traffic, no voices, just wind and the occasional bird.

This is the landscape that shaped Irish imagination—bleak, beautiful, slightly unsettling, full of hidden depths. Stand still long enough and you understand why Irish mythology is full of shapeshifters, why the síde (fairy folk) lived in mounds, why the Otherworld was always just beneath the surface. Bogs feel like threshold spaces, neither land nor water, neither living nor dead.

The bogs also tell Ireland's colonial story: the British drained and cut them for fuel, destroying ecosystems and livelihoods. Bord na Móna, the state peat company, continued industrial harvesting for decades. Now, with climate awareness, there's a push to rewild them. The bogs are recovering, slowly, like Ireland itself.

Spend an hour alone in a bog. No photos, no podcast, just walking and noticing. It's meditation through landscape—the Irish version of mindfulness, grounded not in sunny optimism but in accepting that beauty and bleakness, life and death, are inseparable.

Drink in a Daytime Pub (On a Tuesday)

Everyone knows Irish pub culture. What they don't know: the real magic happens on Tuesday at 2 PM, not Saturday at midnight.

Find a rural pub—not a gastropub, not a tourist venue, just a small-town local. Places like John Benny Moriarty's in Dingle, Dick Mack's also in Dingle (yes, Dingle has excellent pubs), or any nameless establishment in villages across Clare, Kerry, Mayo, Donegal. Arrive mid-afternoon on a weekday.

Inside: dim lighting (Irish pubs are allergic to bright lights), dark wood, possibly a turf fire, a few elderly men nursing pints, the barman who might also be the owner, probably a dog sleeping somewhere, faded photographs of dead locals, a hurling trophy from 1987.

Order a pint of Guinness. Not because it's Irish but because it's what the regulars drink, and watching a proper pour—the slow settle, the perfect head—is its own ritual. Don't rush the barman. It takes two minutes minimum. This isn't slow service; it's craft.

Sit. Don't immediately strike up conversation. Let the rhythm of the place reveal itself. The regulars will be discussing something—local politics, farming, who died recently (death is a constant conversational topic in rural Ireland), or just engaging in the fine art of saying nothing particularly important in the most elaborate way possible.

Eventually, someone will nod at you. This is your cue. You nod back. Later, someone might ask where you're from. Answer honestly but briefly—Irish conversational culture rewards understatement. If you're lucky and the timing is right, you'll be drawn into conversation. If not, that's fine too. Presence is participation.

What you're witnessing: the Irish pub as community center, therapy session, and theater. These places are where rural Ireland processes life—births, deaths, political shifts, weather patterns, local scandals. They're also refuges from the domestic sphere, especially historically for men, though this is changing as younger generations and women claim space.

The daytime pub also reveals something about Irish drinking culture that tourists miss: it's not primarily about getting drunk (though that happens) but about having a socially acceptable excuse to sit, talk, and be among others. The pint is permission to stay, to belong, to be human in company.

Stay for two pints. Three if conversation flows. Pay and leave. You've just participated in an Irish ritual that's simultaneously sacred and mundane, ancient and ongoing.

Learn What the Gaeltacht Actually Means

Ireland's first official language is Irish (Gaeilge)—a fact that surprises visitors since nobody seems to speak it. Except in the Gaeltacht—designated Irish-speaking regions, mostly on the western seaboard and islands.

The Gaeltacht isn't a theme park. It's where the language survived colonization, where it's still the community's primary tongue, where road signs are in Irish first and English second (or not at all), where you'll hear teenagers texting in Irish, grandmothers gossiping in Irish, Mass conducted in Irish.

Visit Connemara's Gaeltacht—around Carna, Rosmuc, Carraroe. Or the Dingle Peninsula's Gaeltacht around Baile an Fheirtéaraigh. Or the Aran Islands, where Irish is everywhere. Stay in a local B&B or rent a cottage. Shop at the small Centra or Spar. Eavesdrop (it's not rude if you don't understand the language).

You'll notice something strange: Irish doesn't sound like the stilted textbook Irish that schoolchildren learn. It's rapid, colloquial, full of English loan words ("rinne mé enjoy é"—I enjoyed it), totally alive.

The Gaeltacht is also where Irish culture feels least self-conscious. There's no performing for tourists because tourists are rare and irrelevant. People fish, farm, work in local government offices, live their lives through Irish without thinking about it as a political statement—though it is, implicitly, an act of cultural survival.

Attend a traditional music session in a Gaeltacht pub—Tí Joe Watty's in Carna, Tigh Mhíchíl in Dingle. The music might include sean-nós singing—unaccompanied, highly ornamented, emotionally raw, often in Irish. It's utterly different from the jigs and reels tourists expect. It's older, stranger, closer to Arabic music in its microtonal bends and ululations than to anything British.

You won't understand the words. That's not the point. You're hearing a language that survived attempted erasure, that carries centuries of collective memory, that sounds like wind and rain and stone walls.

The Gaeltacht reminds you that Ireland is colonized and decolonizing simultaneously—the language is reviving (Dublin has Irish-speaking neighborhoods now, TG4 produces Irish TV, young people learn it voluntarily), but it's also still endangered. The future is uncertain. Which makes the present—hearing it spoken naturally, casually, alive—all the more precious.

Walk Kilmainham Gaol in Silence

Everyone visits Dublin's Kilmainham Gaol—the Victorian prison where the leaders of the 1916 Easter Rising were executed, where Irish revolutionaries were held before and after independence. The tours are excellent, historically detailed, emotionally powerful.

But here's what to do: take the tour, absorb the history, then return to the execution yard at the end. Stand there alone if possible. Be quiet.

Fourteen men were executed here by firing squad over nine days in May 1916. Their rebellion had lasted six days, killed hundreds, and was initially unpopular among Dubliners. The executions changed everything—turning failed rebels into martyrs, galvanizing independence sentiment, setting in motion events that led to the War of Independence, the Civil War, partition, and the Ireland that exists today.

The yard is small, plain, with a cross marking where James Connolly was tied to a chair (too wounded to stand) and shot. It's utterly ordinary, which makes it more affecting. History happened here—not abstract history but fourteen specific men dying specific deaths that changed a nation's trajectory.

What Kilmainham teaches: Irish independence is recent, violent, and unfinished (Northern Ireland remains contested). The romanticization of rebellion—the songs, the martyrology, the heroic narrative—coexists with brutal reality. And Ireland's relationship with its revolutionary past is complicated: proud but also exhausted, celebratory but also critical, aware that the ideals died with the executed leaders and what followed—civil war, conservative Catholic domination, economic stagnation, emigration—was far messier than anyone imagined.

After Kilmainham, walk through the neighborhoods around it: the Liberties, Stoneybatter. These are working-class Dublin areas being rapidly gentrified. Old flat complexes, Georgian tenements once housing families in single rooms, pubs that haven't changed in decades. This is the Dublin that fought for independence—not middle-class professionals but laborers, the urban poor who had little to lose.

Then walk to the city center. Dublin is now wealthy—tech campuses, craft coffee, co-working spaces, rents that locals can't afford. Two Irelands, separated by a century and a economic transformation, visible in a single walk.

Eat a Breakfast Roll (and Understand Class)

The breakfast roll—a soft white baguette filled with fried eggs, sausages, bacon, hash browns, and your choice of condiments—is Ireland's working-class food icon. You buy it at Centra, Spar, or any corner shop. It costs €4-5. Construction workers, tradespeople, truck drivers, and anyone working early shifts eat them.

The breakfast roll is also a class marker. Middle-class Ireland eats porridge with berries or avocado toast. Working-class Ireland eats breakfast rolls. And in a country still navigating rapid class stratification—from poverty to Celtic Tiger wealth to recession to recovery—food choices signal identity.

Order a breakfast roll from a Centra or Supermac's (Ireland's homegrown fast-food chain, beloved with defensive patriotism). Eat it in your car or on a bench. It's greasy, satisfying, utterly unpretentious.

Then notice who else is eating them: the guys in hi-vis vests, the taxi drivers, the delivery workers. These are the people who built Celtic Tiger Ireland—literally, in construction—then lost jobs in the 2008 crash, then rebuilt again. They're the Ireland that doesn't appear in tourism marketing but keeps the country functioning.

While we're on food, try actual Irish cuisine beyond stew and soda bread: boxty (potato pancakes), coddle (Dublin's traditional sausage and potato stew), crubeens (pig's feet, increasingly rare), black and white pudding, and a proper Irish breakfast—not in a hotel but in a working-class café where builders eat.

Also: chipper culture. The local chipper (fish and chip shop) is an Irish institution. Eat chips with salt and vinegar, possibly curry sauce or garlic sauce. Eat them from the bag, standing on the street, slightly drunk, at 11 PM. This is Irish fast food—not breakfast rolls but the late-night meal that concludes every night out.

Food in Ireland isn't sophisticated—the country was too poor for too long for complex culinary traditions to develop outside the wealthy. But it's honest, filling, and deeply tied to class identity. Breakfast rolls, chippers, and builder's tea (strong, milky, sweet) are working-class Ireland's cuisine, as meaningful as any Michelin-starred restaurant.

Witness a GAA Match and Understand Tribalism

The GAA—Gaelic Athletic Association—governs hurling and Gaelic football, indigenous Irish sports that most foreigners have never heard of. These aren't quaint folk traditions; they're serious athletic competitions that inspire tribal loyalty stronger than soccer ever could.

Attend a county match—ideally a hurling match in Munster (Cork, Tipperary, Limerick, Clare, Waterford—these counties live for hurling). The sport is insane: helmeted players wielding ash sticks (hurleys) hit a small ball (sliotar) at speeds exceeding 100 mph, while running, jumping, and physically battling opponents. It's hockey meets lacrosse meets violence, impossibly fast, genuinely dangerous.

The crowds are families, elderly folks, teenagers, entire towns emptied out to support their county. The atmosphere is passionate but not violent—GAA crowds are remarkably well-behaved compared to soccer crowds. County loyalty is absolute: people identify by county first, Ireland second.

This matters because Ireland is small—about the size of Indiana—but county identities remain fierce. A person from Cork and a person from Dublin might as well be from different countries in their own minds. The GAA maintains this tribalism, celebrates it, even while promoting national unity.

The GAA is also amateur—players aren't paid, even at the highest levels. They train intensely while holding regular jobs. This amateurism is fiercely protected as part of the GAA's identity: it's sport for community, not profit.

After the match, go to whatever pub is nearest the stadium. It'll be packed with fans dissecting every play, celebrating or mourning, arguing intensely about decisions made milliseconds apart. Buy a round. Listen to the analysis. You're witnessing Irish oral culture at full throttle—the storytelling, the exaggeration, the eloquent ranting that turns a sporting event into epic narrative.

Sit in a Graveyard and Read the Headstones

Irish graveyards—particularly old ones attached to ruined churches or abbeys—are history lessons carved in stone. They're also surprisingly social spaces: people visit regularly, tend family plots, stop to chat with neighbors doing the same.

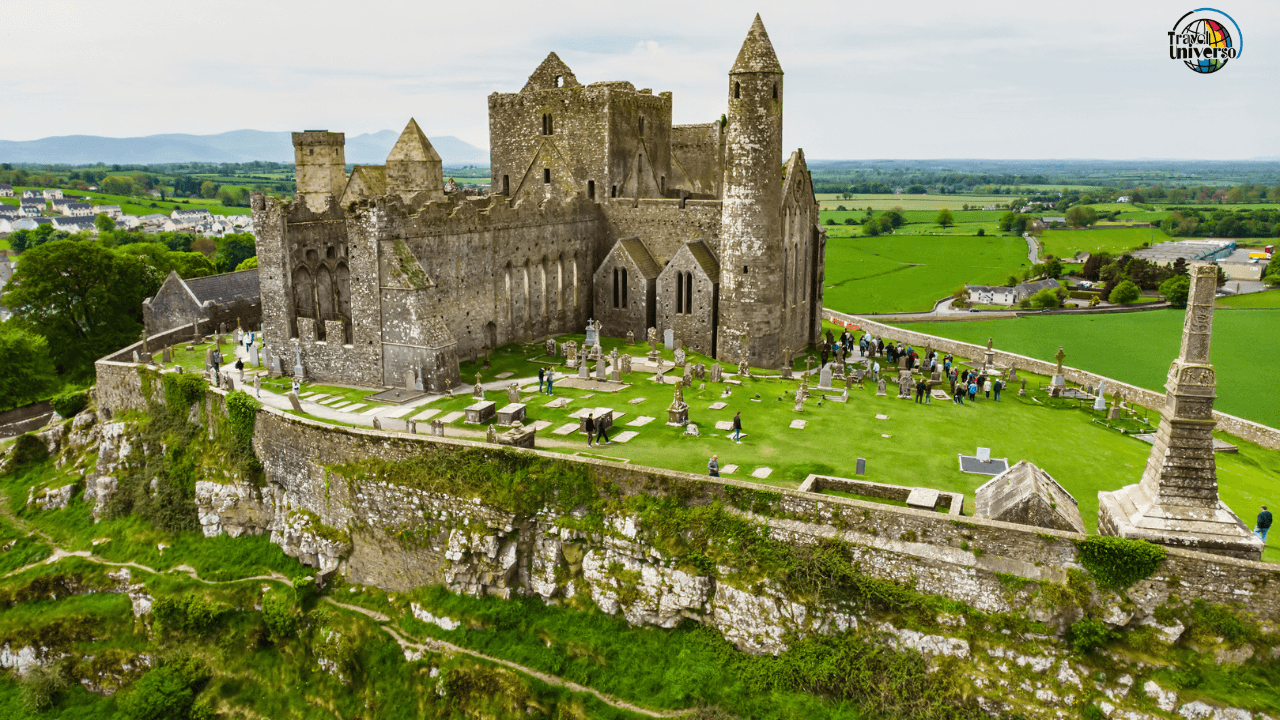

Find an old graveyard in a rural area—there are thousands. Murrisk Abbey near Croagh Patrick in Mayo, Muckross Abbey in Killarney, any medieval ruin with attached cemetery. Walk slowly. Read the stones.

You'll notice patterns: massive infant mortality (stone after stone marking children who died before age five), famine deaths (1847-1849 appears repeatedly), families wiped out by emigration (headstones marking family members who died abroad—Boston, New York, Liverpool), impossible longevity (people living to 95 on subsistence diets), IRA volunteers (commemorated with military honors), priests and nuns (buried with elaborate monuments despite vows of poverty).

The stones tell Ireland's story more honestly than museums: poverty, disease, famine, emigration, violence, faith, resilience. Every family has dead children, missing generations, trauma encoded in dates.

Modern Irish graveyards continue the tradition: elaborate headstones with photos, personal messages, sometimes even benches for visitors. Death in Ireland isn't hidden or sanitized—it's integrated into community life. People talk about the dead constantly, visit graves weekly, maintain bonds with the deceased that feel alive.

This comfort with death—morbid to outsiders, natural to Irish people—shapes the culture: the fatalism, the dark humor, the sense that tragedy is expected and must be endured with dignity and maybe a drink. Joyce called Ireland "the old sow that eats her farrow." It's harsh but not entirely wrong—Ireland consumed its own people through famine, emigration, and poverty for centuries. The graveyards remember.

The Lesson Ireland Teaches

If Mexico City teaches thriving in chaos, Ireland teaches something quieter but equally essential: endurance. Not triumphant survival but persistent, unglamorous, often melancholic endurance—weathering famine, colonization, poverty, emigration, religious control, economic collapse, and still getting up the next morning, making tea, carrying on.

There's a Irish phrase: "níl aon tinteán mar do thinteán féin"—there's no fireplace like your own fireplace. It captures Irish longing: for home, for belonging, for a place that's yours even when circumstances force you to leave. Millions of Irish left—to America, Britain, Australia—but carried Ireland with them, built Irish communities abroad, sent money home, returned when they could or couldn't.

Ireland is emptier than it should be. The population today (about 7 million for the whole island) is less than in 1841 (over 8 million). Famine and emigration hollowed the country. That absence haunts everything—the abandoned cottages, the graveyards full of children, the songs about leaving, the knowledge that this small island's diaspora numbers 70 million worldwide.

You feel this in the bogs' silence, in the Gaeltacht's struggle to maintain language, in Kilmainham's execution yard, in the daytime pub where old men nurse pints and remember who's gone. Ireland is shaped by loss, by absence, by the people who aren't there.

But here's what's remarkable: Ireland endured. The language is reviving. The economy transformed. The Catholic Church's power collapsed. Young people are staying or returning. The future feels open in ways it hasn't for generations.

The Ireland in the guidebooks—leprechauns and Guinness and Celtic mysticism—is marketing. The real Ireland is the breakfast rolls and GAA matches and daytime pubs, the bogs and graveyards and Gaeltacht villages, the working-class estates and tech campuses, the rain that falls sideways and the sudden sun that makes everything glow green, the history that's recent enough to hurt and the future that's uncertain enough to hope for.

And it's been there all along, just beyond Temple Bar and the Cliffs of Moher, in the ordinary places where Irish people live Irish lives—enduring, remembering, carrying on, finding beauty not despite the bleakness but woven through it, inseparable, true.

Get our travel tips, itineraries and guides by email

Sign up for my newsletter!

Name

Let us know what you think in the comments!

Newsletter

Subscribe to the newsletter and stay in the loop! By joining, you acknowledge that you'll receive our newsletter and can opt-out anytime hassle-free.

© 2026 Travel Universo. All rights reserved.